Immigration - The Facts

the most effective way to lower immigration is by reducing temporary migration. In practice, this requires restricting what is by far the largest group of temporary migrants — international students. by Nico louw.

First published in the MRC’s Watercooler newsletter. Sign up to our mailing list to receive Watercooler directly in your inbox.

Immigration has become one of the most politically charged and salient issues across the Western world. This has seen growing electoral success for parties such as Reform in the UK, National Rally in France, Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, Progress Party in Norway, and the Sweden Democrats.

Australia is no exception to this trend, which is showing up as growing support for One Nation. Time will tell whether this support is a temporary protest or something more permanent.

Australia is, however, unique.

In almost every country, this debate is strongly linked to illegal migration and a perceived or real loss of control over borders. In contrast, following the success of Operation Sovereign Borders, Australia has highly effective control over our borders.

Australians have historically been more willing to accept higher levels of legal migration when they believe the Government has control of the borders. In recent years, this relationship has broken down, as legal migration surged at the same time as a rising cost of living, high housing costs and a sense of fragmenting social cohesion.

Recent polling has consistently shown that a majority of Australians now believe immigration is too high.

Despite the importance of immigration policy, the level of detail in the political and media debate has been lacking. Few journalists or political leaders, let alone average voters, could tell you how our immigration system works or what the Government can do to change it.

With that in mind, it is worth setting out the facts. The numbers show that the most effective way to lower immigration is by reducing temporary migration. In practice, this requires restricting what is by far the largest group of temporary migrants — international students.

There are two different migration numbers that are commonly referenced in Australia, and often confused:

1. Net Overseas Migration (NOM):

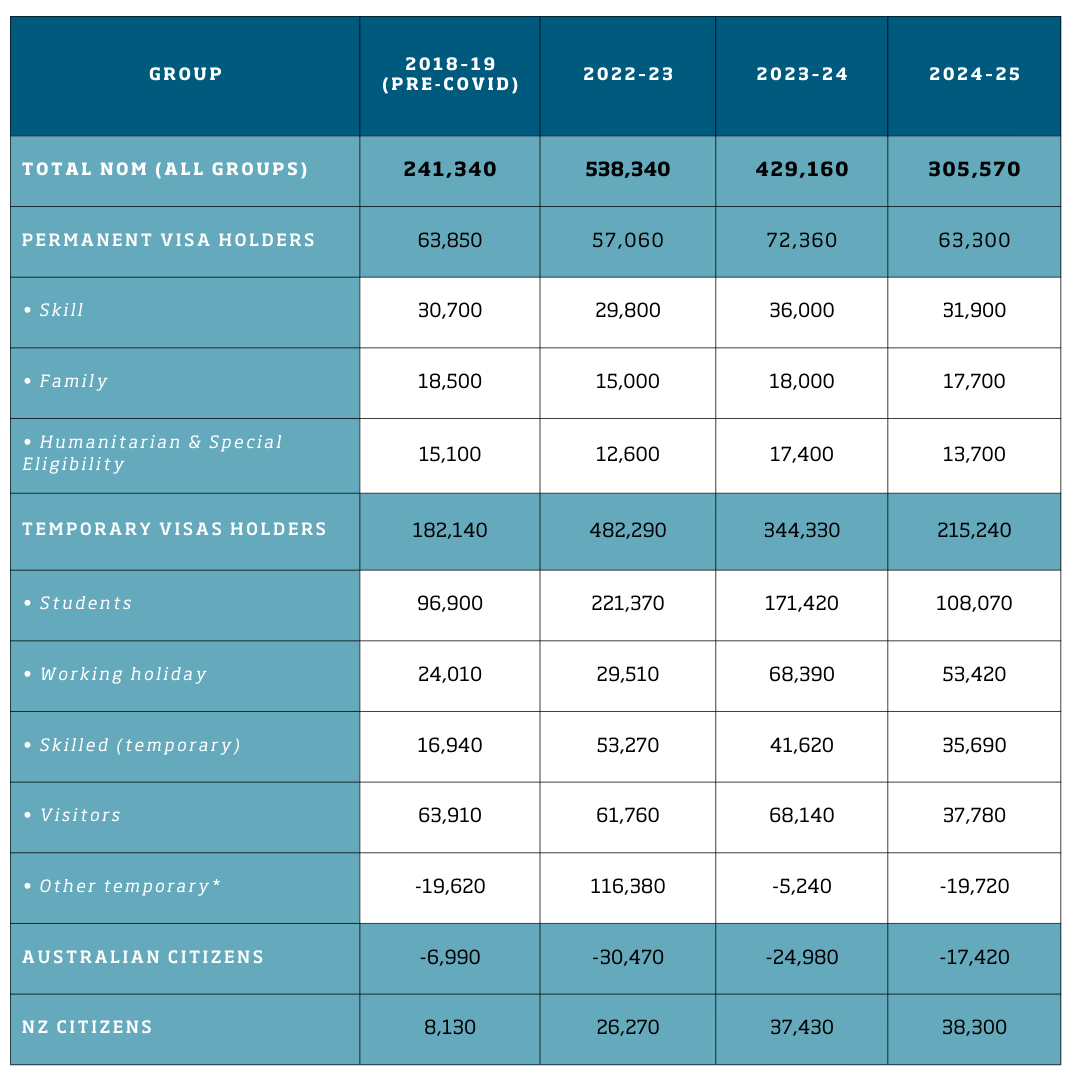

This is the net change in Australia’s population from people moving in and out of Australia. In 2023-24 it was 429,160 and in 2024-25 it was 305,570.

NOM excludes most tourists and business travellers, because it does not count people who are not here long enough to be considered relevant to population statistics (defined by the ABS as people here or away fewer than 12 out of 16 months).

NOM is not a measure of how many visas are granted and there is no policy setting a target number. It is a straightforward measure of the change in population (arrivals minus departures).

NOM increased rapidly post-Covid as temporary migrants such as students returned in huge numbers, but were not matched by people leaving.

2. The Permanent Migration Program:

This is the annual number of permanent visas granted. In 2023-24 it was set at 190,000 and in 2024-25 it was 185,000.

The Permanent Migration program is split between a Skilled Stream and Family Stream (roughly 70% Skilled, 30% Family).

Permanent Migrants can count towards NOM, but only if they are not already here on another temporary visa (in which case they will have already been counted as an arrival).

Understanding the differences between these numbers and the levers the Government can pull to affect them is where the immigration debate quickly gets messy. There are several key things to consider:

1. Around half of permanent migrants are already here when they apply (~60% of those in the Skill stream and 40% in the Family stream). That means the impact of the Permanent Migration Program on NOM is effectively half what you might think. It also means cutting permanent migration has a limited impact if you want to lower NOM.

For example, although the Permanent Migration Program was set at 185,000 places in 2024-25, only around 70,000 people arrived from overseas on Skill and Family permanent visas that year.

The impact on NOM was even lower that year, because there were also departures of permanent visa holders. In net terms, the contribution to NOM from Skill and Family visas was around 50,000 in 2024–25. That is to say, the vast majority of the 305,570 NOM that year was driven by temporary migrants.

2. The exception to this rule is Humanitarian visas, the vast majority of which are unsurprisingly granted offshore (~90%). Migrants on humanitarian visas are the most costly for the Budget, but the numbers are relatively small in the scheme of NOM (the Albanese Government increased the intake from 13,750 to 20,000).

It is important to note that Humanitarian visa holders are counted as permanent migrants in the NOM, but they are separate from the formal Permanent Migration Program.

3. Temporary migration is made up of four key groups: Students, working holiday makers, skilled (temporary), and visitors. Arguably, students are the category where the Government could have the most impact on NOM with the least economic downside.

Students are by far the largest group. Many students stay after they study, on Temporary Graduate Visas, so do not depart Australia for many years. Many will become permanent residents and never depart (and don't bring down the NOM).

Working Holiday visa holders are much smaller in number, time limited, and are meant to depart by design. Those who stay are generally skilled enough to be sponsored by employers.

Temporary skilled workers should, by definition, be here to fill a specific temporary need.

Visitor numbers are outside the Government's control.

4. Temporary migrants can stay here for a long time. There are 2.9 million temporary migrants in Australia, accounting for around 10% of the population.

5. New Zealanders come to Australia on a special visa that gives them uniquely open access to live, study and work here indefinitely. They are a relatively smaller but still important complicating factor for the NOM, accounting for around 1 in 8 net arrivals in 2024-25.

It is possible that the Albanese Government's decision to introduce a direct pathway to citizenship for NZ citizens on special visas in 2023 is driving a higher number of net NZ arrivals in the last two years.

The impact of these key factors on NOM is shown in the data below.

Net Overseas Migration

* Includes all temporary visa holders who don't fit in the other categories, such as Bridging Visas and Temporary Graduate Visas. The large increase in 2022-23 was due to the impact of the Covid Pandemic Event visa, backlog of Bridging visas and extension of Graduate visas.

So, what is the upshot of all this? There are essentially three key takeaways to remember as the immigration debate continues in the months and years ahead.

The Permanent Migration Program is only a small part of the net migration story. Half of skilled and family migrants are already here, so the impact of cutting the program is limited.

In addition, skilled migrants make up 70% of the permanent program. These migrants are younger than the average population and contribute the most economically to Australia.

Significantly lowering the NOM is impossible without reducing temporary net migration.

Assuming that most temporary skilled migrants are filling a specific need, this leaves only working holiday visas and students as categories that could be significantly reduced.

Reducing net temporary migration doesn't need to be limited to reducing arrivals.

There are 2.9 million temporary migrants in Australia. Policy changes that increase departures of these migrants would also reduce net migration, potentially significantly in the short term.

Faced with very similar challenges to Australia, the (left wing) Canadian Government explicitly targeted reductions in temporary resident numbers, with the stated goal of reducing temporary residents to 5% of the population by the end of 2026 (compared to 10% in Australia).

The Canadian Government:

Capped international study visas, reducing the number of new student arrivals;

Tightened post-study work pathways, reducing the number of students who stay after study, and reducing the incentive to come study in the first place; and

Restricted work rights for the spouses of international students and foreign workers, reducing the number of accompanying migrants and the incentive to come to Canada.

The outcome? Canada's population actually fell by 76,000 (-0.2%) in Q3 last year. This was driven entirely by a drop of 176,479 temporary migrants, accounting for around 1 in 17 of all temporary migrants in Canada.

Australia has different immigration settings to Canada and our immigration debate will have its own nuances. But for anyone serious about reducing net migration in line with the wishes of the majority of voters, the Canadian approach to temporary migration would be a good place to start.