News Archive

BUSINESS AND ECONOMY

Albanese’s big-spending agenda parallels Gough Whitlam’s huge expansion of government. Where the two leaders diverge is in their boldness and vision. By Ted O’Brien.

After three years of Labor’s economic mismanagement, the budget has plunged from a $16 billion surplus to a $10 billion deficit. By Ted O’Brien.

The industrial relations reforms of the 1980s are being dismantled and centralised control painfully reconstructed under the Albanese government. By Pru Goward.

Sussan Ley makes the case for moving from dependency to empowerment in a speech to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia.

Ted O’Brien previews the Government’s economic reform roundtable in a special address to the Menzies Research Centre.

The economic outlook for Australia is bleak under a government bereft of ideas and courage. By Nick Cater.

Labor’s super tax won’t eat the rich, but eat the young by denying their aspirations in the short term and stealing their savings in the long term. By Ted O’Brien.

What happens when savers are punished and dependency is rewarded? By Nick Cater

Matt Hancock and Daniel Andrews both embody the kind of politician that Robert Menzies called out decades earlier during the height of World War Two – those who cultivate a fear-based narrative out of fear of losing their grip on power. By Nick Cater.

The state apparatus built to enforce lockdowns is now being deployed to shame the unvaccinated. By Nick Cater.

Locked down Victorians are still waiting for their dividend from Dan Andrews’ April 1st investment into the health system. By Beverley McArthur.

Daniel Andrews has once again taken to whacking the virus with a sledgehammer to cover up his government’s bureaucratic ineptitude. By Nick Cater.

Daniel Andrews is dragging Victoria and the nation deeper into an economic hole than we would have reasonably imagined at the start of last month. By Nick Cater

We are trapped in the vortex created by a Premier without the courage or imagination to challenge the medical experts and chart a different course other than the one that has demonstrably failed. By Nick Cater.

In contrast to Victoria, the NSW story during the COVID-19 pandemic is one of greater competence and coordination, and more capable execution. By Tim James.

A new report from the MRC says the cost of lockdown measures vastly outweigh the benefits

Politics

Fighting for housing supply and tax reform requires more from MPs than signalling to their electorate. It requires them to show the courage and conviction to fight for core beliefs that might be electorally unpopular but are in the public interest. By Jason Falinski and Tim Wilson.

The most commonly heard objection to the Voice is anything but discriminatory. At its heart, the notion of special treatment for anyone offends the Australian spirit of egalitarianism. By Nick Cater.

Australians have a choice at the next election between a clean energy future founded in practical reality or one driven by dogma and wishful thinking. By Nick Cater.

The Liberals must reframe its message to cut through in a digital world and meet young people where they are at. By Freya Leach.

Despite much trumpeting by the WA police force over its drug busting efforts, data shows that the state’s meth problem has only gotten worse. By Kevin McDonald.

Jacinta Ardern’s call to limit online misinformation may be made with noble intentions. But as with many progressive ambitions, the risk of mission creep is very real. By Nick Cater.

Parochial policy reforms that double-tax interstate property investors will only exacerbate Queensland’s housing crisis. By Amanda Stoker.

The Greens have nailed the art of engaging with a new generation of asset-poor voters who are increasingly cynical and distrustful of the two-party system. By Amy Teakle.

Energy and environment

The policy of cutting emissions 'whatever the cost' is no longer sustainable. It weakens our competitiveness, burdens our industries, and treats the public with contempt. By Nick Cater.

Investing in gas pipelines will deliver a clear return to the nation through cheaper electricity prices and higher productivity. By Nick Cater.

Labor is sabotaging Australia’s energy security with a renewables-only policy that will see 90% of 24/7 baseload power exit the system over the next decade. By Ted O’Brien.

Following our recent MRC report into electricity prices, MRC Senior Fellow Nick Cater has been actively exploring new arguments in support of nuclear power. As Nick’s recent work has found, the claim that renewable energy is cheapest is easily refuted by examining comparative electricity costs across Europe. Countries that invest in nuclear have consistently cheaper prices than those that do not.

Finland’s pro-nuclear Greens Party sets a new path for cleaner, cheaper and consistent power. By Nick Cater.

We can meet our three national goals of cheaper, consistent and cleaner power. But only with the right energy policy. By Peter Dutton.

Australia has slipped to 10th place in the OECD rankings of end-user power prices. Of the nine countries where electricity is cheaper, six have nuclear power stations. By Nick Cater.

Nuclear energy has a vital role to play in supporting our energy transition, writes Amir Gazar for the Centre for Youth Policy.

liberal party

Liberal Party founder Robert Menzies’ creed of Australian Liberalism was informed by the ideas of three thinkers from Victorian Britain. By David Furse-Roberts

Tom Hughes was a great Australian and giant of the Liberal Party. He shines as a great example of dedication to the nation and putting public service and nation before self.

Brendan Nelson reflects on the craft behind writing and delivering some of his most memorable speeches.

The Coalition’s plan to get Australia back on track is underpinned by a vision for our country aligned with the expectations and aspirations of everyday Australians, says Peter Dutton as he addresses the Liberal Party’s 64th Federal Council.

media

A 2021 report generated during the height of a global pandemic pointing to misinformation and disinformation concerns does not justify current proposals to grant Australia’s media regulator excessive powers. By James Mathias.

The Albanese Government has released a new Misinformation Bill that would have a huge negative impact on our freedom of speech. It needs to be stopped because no government should tell us what we can and cannot say. By David Coleman.

Australia was a world leader in standing up to the social media giants on publishing online content. But in the vital area of empowering parents to protect their children online we have slipped behind. By James Mathias.

Smart phone technology means the most dangerous place for children is alone in their own bedroom. By Nick Cater.

culture

The proposal to ban YouTube for under-16s is overreach based on flimsy evidence. By Nico Louw.

At a time where the prevailing cultural narrative is one of decline, it is important that we develop a positive story and hopeful vision for the future rooted in human flourishing and prosperity. By Freya Leach.

Our national narrative once inspired generations of Australians and gave them hope for the future. But that has changed, with young people today increasingly pessimistic despite growing up in the most technologically advanced and prosperous society in human history. By Alexander Downer.

The Liberal Party must pitch its tent across both the cities and suburbs or risk political oblivion. By Andrew Bragg.

A complacent Australia is displaying a worrying lack of attunement to the dangers that threaten our peace and stability. By John Anderson.

The Prime Minister deserves credit for his refusal to buckle to demands to dis-endorse Katherine Deves as the Liberal candidate for Warringah. By Nick Cater.

Member for Willoughby Tim James gives voice to the enduring principles of Australian Liberalism as he delivers his maiden speech to the NSW Parliament.

Margaret Cameron-Ash challenges the prevailing orthodoxy behind Australia’s foundational narrative. Review by Nick Cater.

unions

The ACTU has published an eight-point plan to steer Australia out of the COVID-19 crisis. It would cause a deep recession and kill jobs. By Nick Cater.

COVID-19 has exposed the poor health of our national wage system, and workers and small business owners are paying for it with their jobs and enterprises. By James Mathias.

Criminal convictions are treated differently in the corporate and union worlds. And it’s not the corporate bosses who are given the privileges. By James Mathias.

You almost need a PhD in industrial relations law to decipher the awards negotiated by some unions. No wonder some managers are confused.

Retirement

The superannuation industry is growing at an alarming rate while neglecting its key objective: to make retirement easier for Australia’s ageing population.

Unlike in Europe, the safest place for the elderly in Australia is in an aged-care facility. This will be news to those who say the industry is in ‘crisis’. By Nick Cater.

Neglect and failure in the aged care sector are grave concerns for all Australians. They reflect poorly on us and ignore the values on which the nation was founded. By Tim James.

The Treasurer this week proposed offering retired Australians new opportunities. The knee-jerk response from many was hackneyed and unhelpful. By Tim James.

indigenous

Australia's first Indigenous federal parliamentarian was a constitutional conservative who held a profound belief in equal citizenship for all Australians. By George Brandis.

The reaction to the torching of Canberra's Old Parliament House by Aboriginal protestors is evidence of the woke-ward drift of both the media and the police force. By Nick Cater.

Brendan Nelson puts forward a practical proposal for bringing together two conflicting narratives of Australian settlement and ending the controversy over Australia Day.

To meaningfully close the gap with Indigenous Australians, we must simplify the focus areas down to three practical targets. By Andrew Laming.

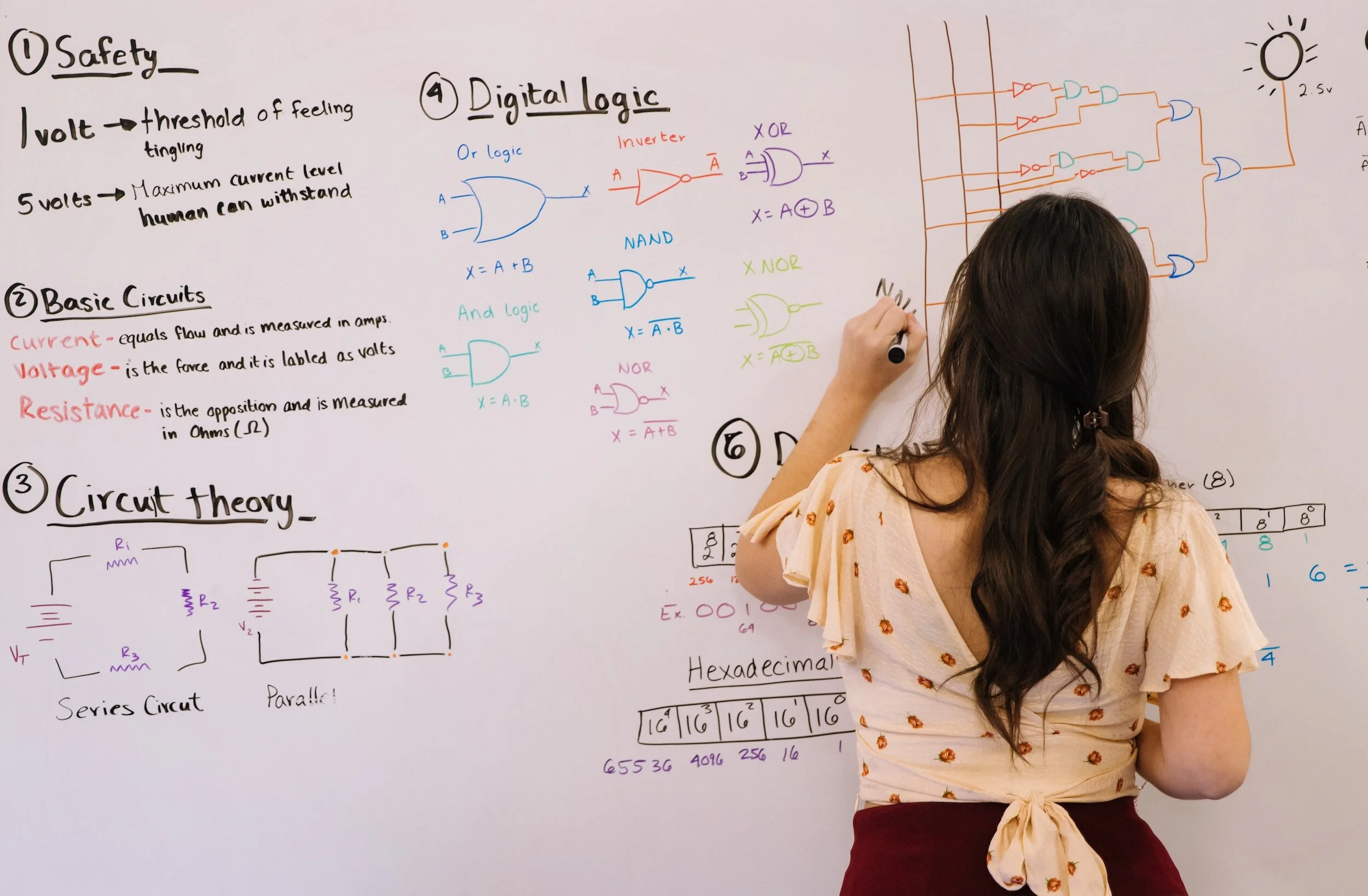

Education

Over the last 20 years, Australian Year 10 students have gone backwards in their schooling by one full year. The government must take the tough action required to arrest declining academic standards. By Sarah Henderson.

Evidence-based teaching methods and explicit instruction of behaviour are fundamental to building a learning environment that re-engages students in the classroom, says Sarah Henderson as she addresses the Independent Schools Australia Forum.

The Albanese Government needs to focus on the foundations of a good education – reading, writing and mathematics – by mandating evidence-based teaching methods. By Sarah Henderson.

Australian teachers find it more difficult to control their classrooms compared with their counterparts overseas, presenting another challenge to an already-strained education system. By Susan Nguyen.

Health

Remote mental health care, integrated with existing services, is a key part of the Government’s COVID-19 strategy, and will provide a path to a better recovery. By Dr Fiona Martin.

No health minister in Australian history has put greater emphasis on increasing the country’s ability to cope with a pandemic than Tony Abbott. By Henry Ergas.

It’s time to cure Australia of its reliance on foreign-made medicines. By Tim James.

Bad policy is usually devised in response to public anxiety and uninformed commentators. Better solutions are the result of thorough research and calm assessment. By Nick Cater.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE

Jim Molan’s seminal book assessing Communist China’s military strength and Australia’s woeful state of unreadiness was his final and most important act of service to his country. By Nick Cater.

Ex-major general and NSW Liberal Senator Jim Molan paints a frighteningly plausible scenario of a Chinese military strike on the Pacific that would put Australia in the line of fire.

When it comes to the nation’s interests, hard strategic realities take primacy over hurt feelings. By Andrew Hastie.

AUKUS does not orient us towards an anachronistic Anglosphere. It is part of a suite of partnerships Australia has forged across jurisdictions to preserve peace and stability in our region. By Marise Payne.

Public Service

Victorians are at the mercy of a clunky public service led by an incompetent government fixated on bashing the virus into submission. By Nick Cater.

We must invest in digital infrastructure to build resilience against disasters. By Victor Dominello.

Sitting atop the Victorian Government’s legions of public servants is a growing band of highly paid unelected bosses doing the jobs of Ministers. By James Mathias.

The COVID-19 crisis has forced Australia to finally face an uncomfortable truth: our governments are too cavalier with our money. By Tim James.

lEGAL

Our Executive Director, David Hughes, joins 2GB's Chris O'Keefe to talk about fixing Australia’s broken class action system.

MRC Executive Director David Hughes spoke with A Current Affair as part of their investigation into the litigation funding industry.

James Mathias joins ABC Radio to discuss how lax regulatory controls have led to Australia becoming an attractive market for overseas litigation funders, whose lucrative returns come out of the pockets of the victims they’re meant to be representing.

A lack of regulatory oversight has enabled litigation funders to generate massive returns at the expense of victims in class actions. By James Mathias.