A lesson for Canberra—From Athens

Greece’s centre right government under Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has spearheaded the country’s remarkable economic turnaround.

By Nico Louw

First published in the MRC’s Watercooler newsletter. Sign up to our mailing list to receive Watercooler directly in your inbox.

Greece in July usually evokes thoughts of beaches and blue water, not bond markets and bailouts. But this month also marks the anniversary of one of the world’s most remarkable economic turnarounds —one that holds valuable lessons for Australia ahead of the Government’s economic reform roundtable next month.

This month marks ten years since Greece’s far-left Government successfully urged voters to reject a third international bailout, only to backflip and accept it within days.

Greece was in economic freefall. Its economy collapsed by 25 per cent in five years, unemployment reached 28 per cent, and the country’s sovereign debt had been downgraded to junk.

A decade on, Greece’s GDP growth is above the Eurozone average and unemployment has almost fallen under 10 per cent. The government is running a surplus and the debt to GDP ratio is falling. Greece’s sovereign debt has regained investment-grade status and Greece can borrow at lower rates than Australia can. The Economist even declared Greece the world’s top economic performer in 2022 and 2023 (and third last year).

Much of the story of this recovery can be traced back to another anniversary — the election of Greece’s current centre-right government in July 2019, led by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. It is thanks to this government’s reforms that Greece is now hailed as a model for combining fiscal discipline with pro-growth policies.

While Greece’s recovery still has a long way to go — productivity is still a problem and GDP per person is below the EU average — Mitsotakis’ approach shows that the answer to every problem doesn’t need to be more spending and higher taxes.

Mitsotakis got Greece’s fiscal house in order, delivering a surplus of 1.3% of GDP last year, comparable to those delivered at the end of the Howard Government.

Mitsotakis achieved this while cutting the corporate tax rate from 28% to 22% and reducing regulation. This helped ensure that growth was driven by foreign and domestic investment — with foreign investment reaching all time highs — not by consumption funded through debt.

Hard decisions were made, such as freezing bloated public sector salaries and pensions. Funding for schools and hospitals grew, but a focus on controlling administrative costs meant this growth was sustainable and funding was used much more efficiently. Improvements in tax compliance meant more revenue was raised, even when taxes such as the VAT on restaurants were cut.

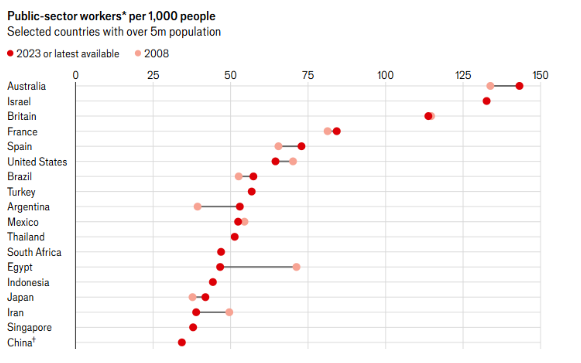

Of particular relevance for Australia is the Greek approach to the public sector, given the Albanese Government’s rapid expansion of the public service. The Economist recently found that, adjusted for population, Australia has the biggest public sector workforce in the world, with 143 employees per 1,000 people —around 29% of workers (this data includes all levels of government).

Chart: The Economist

The Greek Government enacted a public sector hiring freeze and embraced digitisation and red tape reduction as a substitute for workforce growth. A new centralised workplace planning system enabled the Government to reduce hiring in traditional bureaucratic and administrative functions where digitisation had been implemented, and instead prioritise hiring in digital transformation, tax enforcement and public health. The upshot is that public sector wages as a per cent of GDP fell, while maintaining public services.

Greece, once referred to as ‘the sick man of Europe’, is now back on the path to growth and prosperity thanks to the clear agenda of the Mitsotakis Government.

A month out from the Albanese Government’s reform roundtable, we still have no idea what the Government’s agenda is.

This week we did at least get the first honest assessment of the problems we face. Treasury forgot to redact sensitive information when responding to a standard ABC FOI request regarding the “Incoming Government Brief”, the briefing pack all departments prepare for the Government and Opposition during an election. These briefs are one of the few times bureaucrats have the opportunity to lay out everything for their Ministers.

Ironically, it was only due to Treasury’s attempts to cover up their mistake that we know what they said. The ABC completely missed the error at first, only going back to check after Treasury sent a new version and asked for the previous one to be deleted.

It’s thanks to this botched cover up that we know Treasury told Jim Chalmers that the Budget cannot be repaired without raising taxes and cutting spending, and that “tax should be raised as part of broader tax reform”.

We can see why Treasury gave this advice if we look at the Budget forecasts. Spending is forecast to reach 27% of GDP in 2025–26, the highest level since 1986. Revenue is forecast to be 25.5% of GDP, leaving a $40 billion gap.

Listening to the PM and Treasurer talk about the reform roundtable, you’d think that spending isn’t a problem at all, given it’s never mentioned. This reveals much about why we should be deeply concerned about the Government's potential agenda. If they aren’t serious about getting spending under control and you hear the words “tax reform”, it can’t add up unless they really mean “tax increases”.

Unfortunately, the Government seems determined to ignore difficult questions, which means there is no chance their roundtable will result in any serious answers. As other countries grapple with economic resilience and fiscal sustainability, Australia risks drifting into complacency.

The Government still has time to surprise us with a serious reform agenda. But unless it confronts hard fiscal realities and resists the easy path of tax hikes, next month’s roundtable risks becoming just another piece of disappointing political theatre.