The skinny on tax cuts

By David Hughes

First published in the MRC’s Watercooler newsletter. Sign up to our mailing list to receive Watercooler directly in your inbox.

The biggest political issue of the first half of 2024 looks set to be a debate around income tax cuts and broken promises.

Tax reform is complicated. The Government is likely relying on this veil of complexity as a way to shield itself from scrutiny over its broken promise. So I’ll attempt to explain what has happened in plain English.

CONTEXT - OUR INCOME TAX SYSTEM

One of the ways to compare our tax system to other countries is to work out the ratio of our total taxes to the size of our economy. That measure leads some to conclude that Australia is not a particularly high taxing country. The total amount of taxes imposed in Australia represents around 28% of our GDP compared to an average of 33% across the developed world.

However, this is not a complete picture. If we just look at taxes on personal income we find Australia comes close to leading the world. This means Australian governments have a greater reliance on taxing our income than most other nations.

Across the developed world, income tax represents 8% of GDP on average. In Australia, income tax represents over 11% of our GDP and there are only a handful of countries with a greater reliance on income tax.

This overreliance on income tax is bad news according to independent experts at the Parliamentary Budget Office:

‘An over-reliance on any one form of taxation usually means higher rates for that tax, reducing its efficiency. It can also leave government revenues vulnerable to changes in the composition of the economy over time, such as a reduction in the ratio of working age people to the total population associated with demographic change.’

Our income tax system is particularly burdensome at the top end. Our top tax bracket of 45% is one of the highest in the world. There are around 118 countries across the world with a lower headline rate of income tax than Australia (as our analysis shows). This top tax rate of 45% is currently paid by Australian workers earning over $180,000 AUD. In the United States, the top tax rate is only 37% and imposed on workers earning over a mammoth $578,126 USD.

Our income tax system is outdated. Incomes have risen in Australia and workers have been shifted into higher tax brackets at a faster rate than governments have been prepared to lower the tax rates. This means that the average tax rate paid by Australian workers looks set to hit a historic high of 27 per cent in the next decade.

Reform to lower every one of our tax rates is long overdue. The current round of tax reform which we are debating is not new. It was first announced in 2018 and legislated long ago. Before this, we have to go back to the Howard Government to find the last time there were any serious changes to our income tax system announced.

STAGE 3 TAX CUTS

One of the most important aspects to this current debate is the fact that the tax reform package announced in 2018 came in three stages. Stages 1 and 2 benefitted low and middle income earners. While stage 3 seeks to modernise the tax burden for middle and high income earners.

In breaking its promise to deliver the Stage 3 tax cuts in full, Labor has tinkered with several aspects of the rates and thresholds proposed. Most notably, everyone earning over $150,000 now stands to be worse off based on this broken promise.

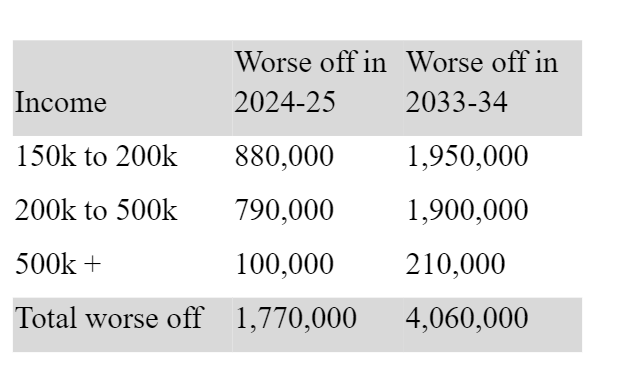

Using the resources of the independent Parliamentary Budget office I’ve calculated how many workers stand to be worse off. As the table below demonstrates, in 10 years’ time, over four million working Australians will be worse off. A large proportion of those will be single income families on incomes of between $150k-$200k.

As the above table demonstrates, bracket creep makes these tax reforms less generous with every year that passes. That's why we have found that the number of Australians in the top tax bracket has doubled in the 16 years since it was introduced.

COST OF THE BROKEN PROMISE

In defending its broken promise, the Labor Government has pointed to the number of low and middle income Australians who will be better off. What they fail to mention is that these workers are also aspirational and will overwhelmingly shift to higher incomes if they continue in the workforce.

Even taking into account population growth and a greater number of taxpayers, the number of low income workers earning between $50k-$75k looks set to decline over the next decade. While the number of workers earning between $150k-$200k is set to grow by over one million (as our analysis in the table below demonstrates).

As a result of Labor’s changes, some voters will get a modest tax cut that they were never promised. While some voters will lose a tax cut that they were promised. A pollster told me last week that the emotional reaction of someone who loses something they were promised is far stronger than someone who gains a new reward. So this decision may end up hurting Labor electorally.

This is compounded by the fact that many low income voters place greater emphasis on the government honouring their promises even though this decision may have benefitted them financially. And if lower income voters actually look into these changes they will realise that they take away some of the incentive for them to earn more in the future.

Peter Dutton has called out this broken promise as a ‘lie’ and he is correct in that characterisation. After all, Albanese indicated there would not be any changes on 100 occasions including less than a week before breaking the promise.

Prime Ministers are not immune to the rules of human nature and we know that one lie often leads to more lies as they seek to cover their tracks. Worse still, breaking one election promise calls into question the integrity of other key election promises. We have already seen Albanese’s colleagues testing the waters and encouraging him to break promises over other taxes such as negative gearing and capital gains.

Let's hope this decision does not open the floodgates to more broken promises where a party who came to government with a small target strategy feels empowered to take on the big targets they ruled out before the election.